Chapter One

Chapter One

RUSSIAN ROULETTE

For the story of Golda Meir, the curtain rises on May 3, 1898. The stage is Russia against a backdrop of civil unrest. Politics, a twisted character in any play, has a leading role to thwart the intentions of Justice. As in Greek mythology, where a mortal human is used to reveal the glory of a noble life, Golda is born with defiance in her DNA. Her script is written by the incorruptible North Star. Let the drama begin…

However, Golda’s story is not a myth. It is an epic legend.

Poverty and filth permeate the masses infecting their kindness like a Black Plague of the heart. Diverting any attention from the true source of this misery, the Russian government aligns with the church to place the blame on liberalism where the principal proponents of this sin can be found in the community of Jews. Therefore, if Holy Russia is to be saved, then, the progress of Jews must be stopped. This policy can be seen from the top: Catherine the Great referring to the “evil influence” of the Jews down through the courts enacting more laws against the Jews (dating from late 1800s over six hundred laws are passed restricting Jewish life), down to the village pogroms often led by priests.

From 1881-1884, over 200 Jewish communities were attacked. Much like lynchings in America, thepogroms were free entertainment, public affairs which thousands would attend. “The Christians did not raise a finger to put a stop to the plunder and assaults… Many of them even rode through the streets in their carriages in holiday attire in order to witness the cruelties that were being perpetrated.”

As a prerequisite to survival, Jews were obliged to obey laws written only for them. Jews lived in Siberia or within a given geographic area of Russia called “Pale of Settlement.” The term “pale” is specifically picked because it means more than just an area fenced off. “Pale” is a word used to describe an area where one race of people live under the control of another race. The Russian Government was sending the message – Russian Jews are subordinate to Russian Christians. Life within the Pale of Settlement was not a sanctuary from the anti-Semitic violence nor was there justice.

The laws included: No Jews can own property outside of their town. No Jews can become judges, sit on a jury, run their own school (schools must be run by Christians), be employed at the post office or the Stock Exchange or the Department of Railways. No Jews can buy land outside of town to use as a cemetery, or exceed the quota of 5% Jewish surgeons (unless there is a war). Jews moving from town to town within the Pale or wanting to move outside the Pale must have special permission (Jewish prostitutes are exempt from this rule).

Restrictions on Jewish merchants include: If a Jewish shop is for watch repair, it is against the law to sell

a watch chain; a baker can’t sell coffee; and kosher butchers can’t sell to non-Jews. To paralyze the possibilities of the next generation, it is against the law to teach young Jews the Russian language in Hebrew schools. Other laws, with no purpose other than being punitive, stipulate if a Jewish couple can marry, when a Jewish couple can marry, and how many Jewish marriages can take place each year.

Uncertainty was the daily bread of the Jewish citizens under the control of police lining their pockets with bribes. Any person caught standing up for himself would incur his house being raided, his arrest on trumped up charges and then being dragged through the streets (a message to everyone else) and thrown into a jail cell for several days. Worse still, families or whole villages could be given only a three-day notice to pack up and leave.

The legal suffering and persecution listed here is only a wisp of the evidence of Jews being used as a religious deflection by those hiding behind walls of economic advantage. In the years to come, Golda will not forget the lesson that tyranny, not religion, within any group gives rise to corruption and extortion. Future British officials and US officials will insinuate to Golda that she appease Arab extremists, but Golda never forgets that no amount of subservience or bribery will avert despotism.

For now, Golda is a little girl, and her birth name is Goldie Mabovitch. Born to Blume and Moshe, the importance of her parent’s background is this – they are unimportant. They are not the wealthy, not the noble class, and not the intelligentsia. Given these circumstances, it is most unlikely Golda will ever go far unless one notices she is stubborn like her great-grandmother, Buba Goldie. Buba Goldie, dubbed “the man in the family” would have laughed hearing this repeated by the future Prime Minister of Israel, David Ben-Gurion, referring to her namesake as, “The only man in my cabinet.” As they say, the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree

Golda’s parents meet in Pinsk (within the Pale of Settlement) where her mother’s family lives. Moshe Mabovitch has come to town from the Ukraine to register for mandatory military duty. Jewish quotas within the army must be filled or families are ruined with fines beyond their finances. There is also the fact that children are taken by the Russian soldiers. Moshe knows the stories of his grandfather, who was kidnapped when he was thirteen and conscripted into the Russian army for a twenty-five year commitment. The grandfather was lucky and escaped after thirteen years. Moshe, wondering what dangers might befall him on this trip to Pinsk, need not worry. He falls in love.

Blume announces to her family that she met a “tall handsome young man” and she “instantly fell in love.” Golda’s grandmother recognizes Moshe’s integrity and gives this union her blessing.

Over the next few years Blume and Moshe have a daughter, Sheyna. Blume’s next five children, four boys and one girl, will die before their first birthdays due to ill health and disease caused by poverty. When their living conditions improve because Blume is the wet nurse/nanny for a wealthy family, they have their daughter Golda. Golda’s innate strong will is evidenced by her early nickname – Kochleffl – a stirring spoon. One more daughter, Zipke, is born (referred to in future text as “Clara” her name after the family immigrates). Although Blume will continue to struggle with pregnancies and miscarriages, the

three daughters will be the extent of the immediate Mabovitch family.

Moshe, working as an artisan and woodworker, has limited opportunities living in Pinsk. He is not able to provide for his family by staying inside the Pale. However, in order to live outside the Pale he needs permission. Moshe builds a chess table. Proving his skills grants him the special pass he needs to live in Kiev. His optimism sees the wealth of the city and ignores the fact that in all of Russia, Kiev is the most anti-Semitic.

His hard work and a family loan support Moshe building a wood shop. He steps closer to success when he is awarded a contract. He finishes a furniture request for schools and libraries. The officials don’t pay him. Why? They either find out Moshe is a Jew or they knew it and planned the increase in profit from free goods. Regardless, Moshe has no recourse because he has no rights. He is a Jew.

Golda’s earliest memories are of Kiev. Not romanticizing she recalls, “I have very few happy or even pleasant memories of this time.” We “suffered, with poverty, cold, hunger and fear, and I suppose my recollection of being frightened is the clearest of all memories.” Her reference to fear is the night (April 19, 1903) of a pogrom in Kiev. Mobs with knives, crowbars and big sticks screaming “Christ killers” could be heard coming down the street.

Golda recalls, “I remember how scared I was and how angry that all my father could do to protect me was to nail a few planks together…” Her fear as a child and the anger of her inability to protect herself will translate into action in the years to come. Golda will never fall to a victim mentality nor will she engage in polite repartee that diminishes the grim reality of mob violence.

۞ Another child remembers a night in Russia, “lying on a blanket by the side of a road, watching his house burn to the ground.” Immigrating to America, he becomes a great composer. Irving Berlin writes “God Bless America.”

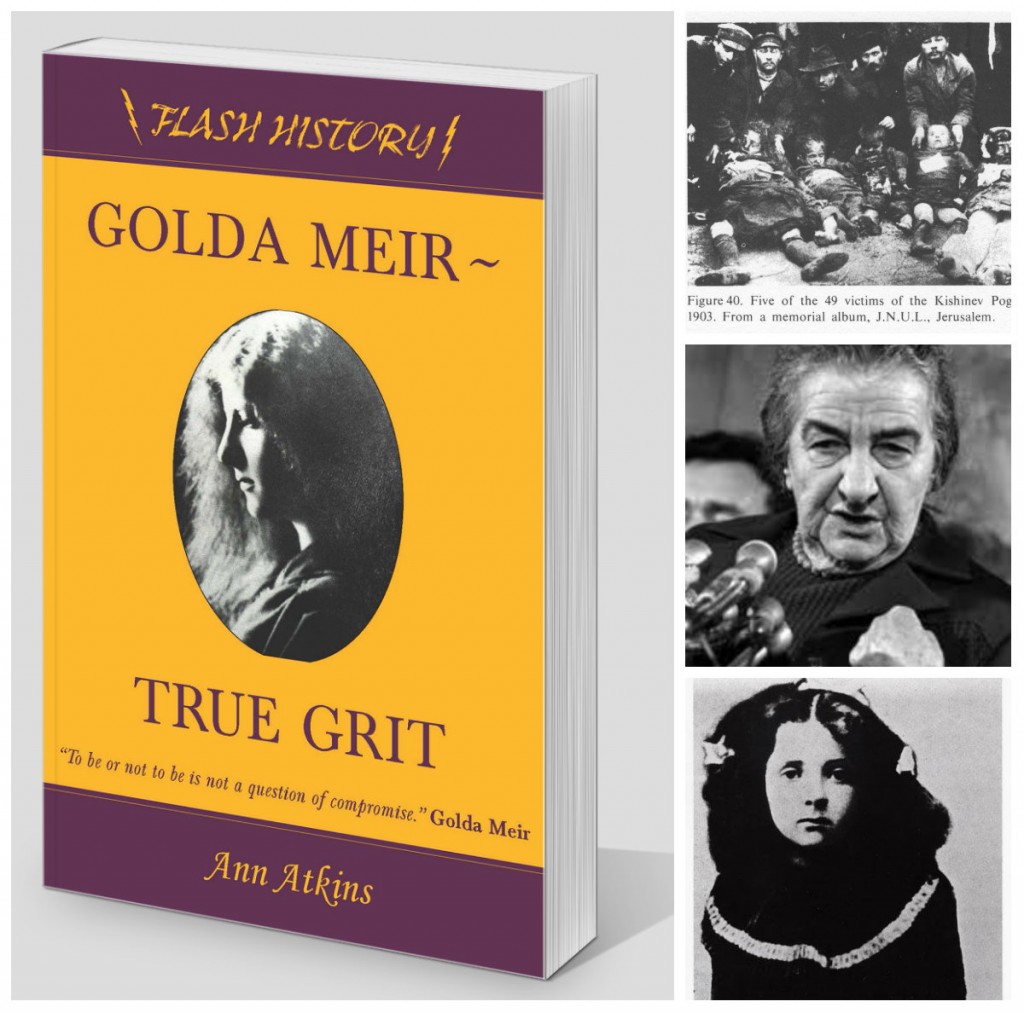

Moshe is unable to succeed against the twisted legal discriminations of Kiev. His family is starving and living with fear, so they return to Pinsk, moving in with his father-in-law. Moshe’s next plan is to immigrate to America. Aside from the cost, going to live on the other side of the world is an enormous decision. It is the 1903 Kishinev Pogrom connected to the poster described earlier in the “Context and Commentary” which pushes him to make the move. Here is an account of what happened during the pogrom:

“Some Jews had nails driven into their heads. Some had their eyes out. Children were thrown from garret windows, dashed to pieces on the street below. Women were raped, after which their stomachs were ripped open, their breasts cut off. Still the police did nothing. Nor did the city officials. Or the so-called intelligentsia. Students. Doctors. Lawyers. Priests. They walked leisurely along the streets watching the show.”

Under the gaze of 5,000 Czarist troops, the wrath of the Kishinev Pogrom lasts three days. Over

2,000 families are homeless because 1,300 homes and stores are looted and destroyed.

1903 – Kishinev Pogrom

Golda will carry these memories of pogroms into her future. With any attempt to understand her life she reminds us, “If there is any logical explanation… for the direction which my life has taken… [it is] the desire and determination to save Jewish children… from similar experience.”

How can Jews protest? What are their options? Take to the streets and fight? They have no army and no guns. They will be murdered and their fewer numbers will mean survival of their race even less likely. Many will immigrate and leave Russia behind. But for those who stay, their protest is to declare a day-long fast.

Golda, just turning five, declares that she will fast. Blume attempts to dissuade her daughter explaining the adults are the ones that will fast. Golda dismisses her mother’s rationale with her own. Golda will fast for the children.

Golda is already living up to the words she would speak later in life, “It isn’t really important to decide when you are very young just exactly what you want to become when you grow up. It is much more important to decide on the way you want to live. If you are going to be honest with yourself and honest with your friends, if you are going to get involved with causes which are good for others, not only for yourselves, then it seems to me that that is sufficient, and maybe what you will be is only a matter of chance.”

Amidst the wave of immigrants that leave after the Kishinev Pogrom, Moshe is one of them. He makes plans to go to America and return in three years with enough money to support his family. Blume and the girls remain in Pinsk.

For Golda, the next few years will provide some warm memories of her grandfather’s house full of aunts, uncles and cousins. Blume, baking bread and selling it door to door, earns enough money for a small apartment for her and her daughters. Although, any image of a cozy life is not totally correct, because next door is a police station. Blume and the girls can hear the screams of men and women being interrogated and beaten. Blume has particular reason to worry. Sheyna, at any moment, could be one of those prisoners.

Sheyna’s involvement in revolutionary activities, like handing out pamphlets to protest the tsar, could get the whole family killed, imprisoned or sent to Siberia. Sheyna is also having illegal meetings at the apartment. Bluma, frantically stays out front to watch for police.

The debates within the Jewish community on how to move forward as a people are over these options: 1. stay in the country and advocate for change within the Russian government; 2. immigrate to another country, assimilate there and hope to not be persecuted; 3. return to the land of their origins and work toward the rebirth of Israel.

Option 3 is called Zionism: The belief of Jews having their own nation state in a territory defined as the Land of Israel. Here, Jews and their Jewish culture will be free of anti-Semitism. Assimilating to a foreign culture in order to escape persecution will not be necessary.

A debate is not necessary if the rights of your citizenship are upheld in your country. But for centuries, in dominions around the world, Jews live in a status of Diaspora in order to survive.

As a Diaspora, Jews are the minorities in any country and as such they are convenient scapegoats for social, economic and government ills. This leads to the growing popularity of option 3 in the debate.

Golda, eavesdropping on Sheyna’s meetings, is learning the pros and cons of each option.

Sheyna is nine years older than Golda. Golda adores Sheyna and describes her as, “a remarkable intense, intelligent girl who became and remained one of the greatest influences of my life.” Sheyna has illegal political meetings at the apartment and Golda, listening from a hiding place, is beginning her education. Golda later explains what she started to learn at such a young age, “I must have begun, when I was about six or seven, to grasp the philosophy that underlay everything that Sheyna did.”

What Golda hasn’t learned yet is to not overstep her bounds. When Sheyna discovers Golda in her hiding spot, Sheyna threatens that Golda be banished from any future meetings. Golda retorts with her own threat. “Look out, or I’ll tell the police what you’re saying.” Sheyna responds, “If you do, I’ll be sent to Siberia and I’ll never return.”

The drama Sheyna brings to the family continues to escalate. Sheyna is in love with Shamai (referred to in future text by his American name, Sam), a fellow revolutionary. Sheyna also learns that Theodore Herzl is dead. Mourning his death, Sheyna will wear only black for the next two years.

“If you will it, it is no dream.”

Theodore Herzl: Like the future Gandhi giving his people hope, Herzl is not only a spokesman for the Jews but a rallying icon of Jews returning to Palestine, the Zionists. In 1902, Herzl publishes a novel Altneuland (Old New Land). Translated to Hebrew the title is – Tel Aviv. He might be surprised to know that someday the title Tel Aviv will be used as the name of a city in Israel. Herzl’s photo will hang behind the signers of the Declaration of Independence for the State of Israel on the day of their independence. Herzl’s quote had come true. “If you will it, it is no dream.”

1948 David Ben-Gurion reads the Declaration of Israeli Independence

From the Archives Department, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries

Any dream for Blume right now is a nightmare. She lives in constant fear of Sheyna being caught by the Cossacks (groups of military horsemen who delight in the dirty work of enforcing laws and taking bribes). Blume’s breaking point comes the day a drunken peasant sees Golda and a friend playing in the street. He grabs their heads and bangs them together yelling, “That’s what we’ll do to the Jews. We’ll knock their heads together and we’ll be through with them.”

Blume writes to Moshe whom she hasn’t seen in three years – “We are coming now.”

Golda has always heard her people say in solemn remembrance at the conclusion of the Yom Kippur service – “Next year in Jerusalem.” Now Golda hears her mother saying – Next year in Milwaukee.